In most mammals, the stomach is a hollow, muscular organ of the gastrointestinal tract (digestive system), between the esophagus and the small intestine. It is involved in the second phase of digestion, following mastication (chewing). The word stomach is derived from the Latinstomachus,[3] which derives from the Greek word stomachos (στόμαχος). The words gastro- and gastric (meaning related to the stomach) are both derived from the Greek word gaster (γαστήρ). The stomach churns food before it moves on to the rest of the body.

This article is primarily about the human stomach, though the information about its processes are directly applicable to most mammals.[4] A notable exception to this is cows. For information about the stomach of cows, buffalo and similar mammals, see ruminants.

This article is primarily about the human stomach, though the information about its processes are directly applicable to most mammals.[4] A notable exception to this is cows. For information about the stomach of cows, buffalo and similar mammals, see ruminants.

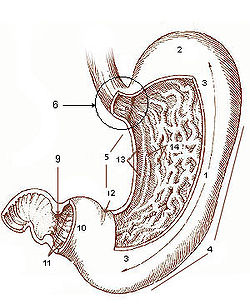

SectionsThe stomach is divided into four sections, each of which has different cells and functions. The sections are:

CardiaWhere the contents of the esophagus empty into the stomach.FundusFormed by the upper curvature of the organ.Corpus BodyThe main, central region.Pylorus or antrumThe lower section of the organ that facilitates emptying the contents into the small intestine.

CardiaWhere the contents of the esophagus empty into the stomach.FundusFormed by the upper curvature of the organ.Corpus BodyThe main, central region.Pylorus or antrumThe lower section of the organ that facilitates emptying the contents into the small intestine.

GlandsThe epithelium of the stomach forms deep pits. The glands at these locations are named for the corresponding part of the stomach:

Cardiac glands

(at cardia)Pyloric glands

(at pylorus)Fundic glands

(at fundus)Different types of cells are found at the different layers of these glands:

Layer of stomachNameSecretionRegion of stomachStainingIsthmus of glandmucous cellsmucus gel layerFundic, cardiac, pyloricClearBody of glandparietal (oxyntic) cellsgastric acid and intrinsic factorFundic, cardiac, pyloricAcidophilicBase of glandchief (zymogenic) cellspepsinogen, renninFundic onlyBasophilicBase of glandenteroendocrine (APUD) cellshormones gastrin, histamine, endorphins, serotonin, cholecystokinin and somatostatinFundic, cardiac, pyloric-[edit]Control of secretion and motilityThe movement and the flow of chemicals into the stomach are controlled by both the autonomic nervous system and by the various digestive system hormones:

GastrinThe hormone gastrin causes an increase in the secretion of HCl, pepsinogen and intrinsic factor from parietal cells in the stomach. It also causes increased motility in the stomach. Gastrin is released by G-cells in the stomach in response to distenstion of the antrum, and digestive products(especially large quantities of incompletely digested proteins). It is inhibited by a pH normally less than 4 (high acid), as well as the hormone somatostatin.CholecystokininCholecystokinin (CCK) has most effect on the gall bladder,causing gall bladder contractions, but it also decreases gastric emptying and increases release of pancreatic juice which is alkaline and neutralizes the chyme.SecretinIn a different and rare manner, secretin, produced in the small intestine, has most effects on the pancreas, but will also diminish acid secretion in the stomach.Gastric inhibitory peptideGastric inhibitory peptide (GIP) decreases both gastric acid and motility.Enteroglucagonenteroglucagon decreases both gastric acid and motility.Other than gastrin, these hormones all act to turn off the stomach action. This is in response to food products in the liver and gall bladder, which have not yet been absorbed. The stomach needs only to push food into the small intestine when the intestine is not busy. While the intestine is full and still digesting food, the stomach acts as storage for food.

[edit]EGF in gastric defenceEpidermal growth factor or EGF results in cellular proliferation, differentiation, and survival.[7] EGF is a low-molecular-weight polypeptide first purified from the mouse submandibular gland, but since then found in many human tissues including submandibular gland, parotid gland. Salivary EGF, which seems also regulated by dietary inorganic iodine, plays also an important physiological role in the maintenance of oro-esophageal and gastric tissue integrity. The biological effects of salivary EGF include healing of oral and gastroesophageal ulcers, inhibition of gastric acid secretion, stimulation of DNA synthesis as well as mucosal protection from intraluminal injurious factors such as gastric acid, bile acids, pepsin, and trypsin and to physical, chemical and bacterial agents.[8]

[edit]Diseases of the stomachMain article: Stomach diseaseHistorically, it was widely believed that the highly acidic environment of the stomach would keep the stomach immune from infection. However, a large number of studies have indicated that most cases of peptic ulcers, gastritis, and stomach cancer are caused by Helicobacter pyloriinfection.

[edit]In other animalsAlthough the precise shape and size of the stomach varies widely between different vertebrates, the relative positions of the oesophageal and duodenal openings remain relatively constant. As a result, the organ always curves somewhat to the left before curving back to meet the pyloric sphincter. However, lampreys, hagfishes, chimaeras, lungfishes, and some teleost fish have no stomach at all, with the oesophagus opening directly into the intestine. These animals all consume diets that either require little storage of food, or no pre-digestion with gastric juices, or both.[9]

The gastric lining is usually divided into two regions, an anterior portion lined by fundic glands, and a posterior with pyloric glands. Cardiac glands are unique to mammals, and even then are absent in a number of species. The distributions of these glands vary between species, and do not always correspond with the same regions as in man. Furthermore, in many non-human mammals, a portion of the stomach anterior to the cardiac glands is lined with epithelium essentially identical to that of the oesophagus. Ruminants, in particular, have a complex stomach, the first three chambers of which are all lined with oesophageal mucosa.[9]

In birds and crocodilians, the stomach is divided into two regions. Anteriorly is a narrow tubular region, the proventriculus, lined by fundic glands, and connecting the true stomach to the crop. Beyond lies the powerful muscular gizzard, lined by pyloric glands, and, in some species, containing stones that the animal swallows to help grind up food.[9]

Cardiac glands

(at cardia)Pyloric glands

(at pylorus)Fundic glands

(at fundus)Different types of cells are found at the different layers of these glands:

Layer of stomachNameSecretionRegion of stomachStainingIsthmus of glandmucous cellsmucus gel layerFundic, cardiac, pyloricClearBody of glandparietal (oxyntic) cellsgastric acid and intrinsic factorFundic, cardiac, pyloricAcidophilicBase of glandchief (zymogenic) cellspepsinogen, renninFundic onlyBasophilicBase of glandenteroendocrine (APUD) cellshormones gastrin, histamine, endorphins, serotonin, cholecystokinin and somatostatinFundic, cardiac, pyloric-[edit]Control of secretion and motilityThe movement and the flow of chemicals into the stomach are controlled by both the autonomic nervous system and by the various digestive system hormones:

GastrinThe hormone gastrin causes an increase in the secretion of HCl, pepsinogen and intrinsic factor from parietal cells in the stomach. It also causes increased motility in the stomach. Gastrin is released by G-cells in the stomach in response to distenstion of the antrum, and digestive products(especially large quantities of incompletely digested proteins). It is inhibited by a pH normally less than 4 (high acid), as well as the hormone somatostatin.CholecystokininCholecystokinin (CCK) has most effect on the gall bladder,causing gall bladder contractions, but it also decreases gastric emptying and increases release of pancreatic juice which is alkaline and neutralizes the chyme.SecretinIn a different and rare manner, secretin, produced in the small intestine, has most effects on the pancreas, but will also diminish acid secretion in the stomach.Gastric inhibitory peptideGastric inhibitory peptide (GIP) decreases both gastric acid and motility.Enteroglucagonenteroglucagon decreases both gastric acid and motility.Other than gastrin, these hormones all act to turn off the stomach action. This is in response to food products in the liver and gall bladder, which have not yet been absorbed. The stomach needs only to push food into the small intestine when the intestine is not busy. While the intestine is full and still digesting food, the stomach acts as storage for food.

[edit]EGF in gastric defenceEpidermal growth factor or EGF results in cellular proliferation, differentiation, and survival.[7] EGF is a low-molecular-weight polypeptide first purified from the mouse submandibular gland, but since then found in many human tissues including submandibular gland, parotid gland. Salivary EGF, which seems also regulated by dietary inorganic iodine, plays also an important physiological role in the maintenance of oro-esophageal and gastric tissue integrity. The biological effects of salivary EGF include healing of oral and gastroesophageal ulcers, inhibition of gastric acid secretion, stimulation of DNA synthesis as well as mucosal protection from intraluminal injurious factors such as gastric acid, bile acids, pepsin, and trypsin and to physical, chemical and bacterial agents.[8]

[edit]Diseases of the stomachMain article: Stomach diseaseHistorically, it was widely believed that the highly acidic environment of the stomach would keep the stomach immune from infection. However, a large number of studies have indicated that most cases of peptic ulcers, gastritis, and stomach cancer are caused by Helicobacter pyloriinfection.

[edit]In other animalsAlthough the precise shape and size of the stomach varies widely between different vertebrates, the relative positions of the oesophageal and duodenal openings remain relatively constant. As a result, the organ always curves somewhat to the left before curving back to meet the pyloric sphincter. However, lampreys, hagfishes, chimaeras, lungfishes, and some teleost fish have no stomach at all, with the oesophagus opening directly into the intestine. These animals all consume diets that either require little storage of food, or no pre-digestion with gastric juices, or both.[9]

The gastric lining is usually divided into two regions, an anterior portion lined by fundic glands, and a posterior with pyloric glands. Cardiac glands are unique to mammals, and even then are absent in a number of species. The distributions of these glands vary between species, and do not always correspond with the same regions as in man. Furthermore, in many non-human mammals, a portion of the stomach anterior to the cardiac glands is lined with epithelium essentially identical to that of the oesophagus. Ruminants, in particular, have a complex stomach, the first three chambers of which are all lined with oesophageal mucosa.[9]

In birds and crocodilians, the stomach is divided into two regions. Anteriorly is a narrow tubular region, the proventriculus, lined by fundic glands, and connecting the true stomach to the crop. Beyond lies the powerful muscular gizzard, lined by pyloric glands, and, in some species, containing stones that the animal swallows to help grind up food.[9]